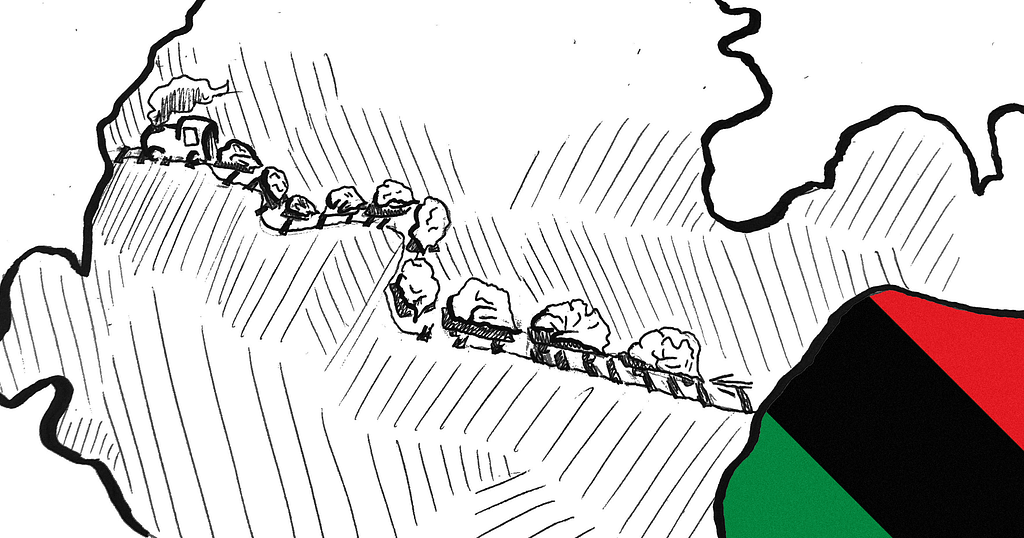

Migrating Minds

On the evolving nature of African “brain drain”

“I came here knowing I was going to go back,’’ Laura Koech, SY ’21, said as she poured steaming water into the mug in front of me. The vanilla scent of the tea gave away its identity long before it reached my mouth. Rooibos tea, an iconic South African beverage, has been one of the country’s most popular exports, making its way into the kitchen cupboards of tea enthusiasts around the world. Finding Rooibos in Yale’s Good Nature Market was a cathartic moment for my fellow South Africans and me during the muddled transition of our first semester; this aromatic little piece of home had made it across the Atlantic long before we did.

“For me, it comes down to responsibility. I feel like I’m responsible to the continent, responsible to the community that got me here. It’s like Superman, right? If he has all that power and just sits in his house, then what’s the point?” Koech laughed. Koech, a junior studying psychology, is hoping to go to graduate school in the U.S. but ultimately intends to return to Kenya for the majority of the 80,000 hours of her career.

But Koech explains that her choice to return to her country of origin places her in the minority with respect to African graduates from the Ivy League. “Out of the 150 or so Kenyans that make it here every year, probably 20 go back,” Koech said, spooning rice onto a plate next to the stove. We sat in her off-campus house on Elm St., the rhythm of raindrops against the window contesting the bass of the Afrobeats pumping out of her speaker. “The rest get caught up in corporates [sic] and research, and that’s great for them individually, and that’s good for their families. But those resources that we need back home are just staying here.”

The concern that Africa’s “intellectual elite” is migrating North, drawn by educational and career opportunities, is not a new one. A steady stream of media headlines detailing the “staggering loss” of talent and young professionals from African countries started appearing during the early 2000s. The slew of articles followed a report from the African Union, a continental body comprising 55 member states, which revealed that 70,000 skilled young professionals emigrate from the continent every year. Former South African president Thabo Mbeki cautioned against the “frightening” development, stating that Africa loses over 10 percent of its skilled information technology and finance professionals to the global North. At the undergraduate level, the U.S. received 31,113 students from sub-Saharan Africa in 2014, and that number has since risen.

But the case against emigration to the global North is hardly cut and dry. “Brain drain” in Africa has become a catch-all term for those seen as abandoning the continent for the smorgasbord of opportunities in the US and Europe; but many believe that they can leverage an Ivy League education and American work experience for the benefit of their countries of origin. While considering the tension between my own noisy subconscious urgings to ‘give back’ to South Africa in some way and my hankering to pursue research in a gleaming U.S. lab, I decided to reach out to undergraduates, professors, and visiting intellectuals with ties to the continent. Through these conversations, we probed how the micro and the macro scales of the emigration question are playing out in the courtyards of the Ivy League.

For those comprising this intellectual exodus, the reasons for emigrating are varied — yet almost all stem from the intractable draw of U.S. opportunities and the potential lack thereof at home. While presidents and continental councils may denounce the phenomenon, for the individual, the criteria for choosing a school remain those of any high school graduate — quality of education and social life, and the opportunities embedded in a framed certificate with the school’s name at the top. But as one draws closer to receiving that certificate, the question of how to use the privilege of a Yale education becomes convoluted. In the midst of the general senior angst about what to do with one’s life post-graduation, the case of the African Yalie is particularly fraught. For many, feelings of responsibility come into conflict with personal ambition and career goals.

“I’m trying not to be another statistic,” Michaellah Mapotaringa, TD ’21, told me. Mapotaringa, a Zimbabwean national and president of the Yale African Student Association, related to me how ties to family sometimes result in students remaining in the global North. “I think often times we’re thinking about how best we can help our families,” she explained. “And there’s a big difference between going back home and being unemployed but being physically there, and staying here and sending money.” Zimbabwe receives an annual average of around 1.85 billion dollars in money sent home by those in the diaspora, and this figure doesn’t account for informal modes of payment that slip through the official net. Across the continent, these payments, known as remittances, are edging towards $45 billion annually.

“I’m constantly grappling with this idea that I want to help my family, but I can’t necessarily do that when I’m at home,” Mapotaringa told me. While Mapotaringa acknowledges that many find themselves caught between struggling economies and limited educational opportunities at home, and a desire to contribute to their families financially, she has made the decision to go home once she graduates. “I want to work in diplomacy on the continent,” Mapotaringa said, brushing her braids away from her eyes. “Or I’ll do economic policy work for a regional organization. I’m more interested in working with smaller organizations that have a lot of day-to-day interactions with people and seeing an impact.” Mapotaringa, who is also majoring in African studies, shared with me her feeling that for her, return was inevitable — the natural product of her academic interests and desire to contribute to Africa’s evolving political climate. “I have yet to figure that out precisely, but I know I’m definitely going to end up on the continent.”

Mapotaringa and Koech are two counterexamples that undermine the “abandon ship” narrative that is being broadcast about youth emigration. Both have decided to pour the education they’ve received here back into the continent, and believe that this will necessitate a geographical move back home.

But according to another junior who would prefer to remain anonymous, there are some fields in which one can best contribute to one’s nation by living an ocean away from it. “We are impacted by decisions [in the U.S.] in which our voices and our concerns aren’t even represented,” he told me. He is particularly interested in contributing to the development of AI, whose algorithms are notorious for being developed by homogenous groups — and consequently discriminating against minorities. “My impetus for wanting to stay here for some time is to work in the tech industry,” he explained. “Because right now they’re developing software that is changing how the whole world interacts with each other and if you do not have a voice…” he trailed off. “All this tech is being implemented in places like San Francisco and South Korea,” he pointed out, “but it’s going to influence everyone.”

The debate concerning whether students and young professionals who move abroad can have a net positive impact on their home countries continues. However, the tangible corollary to emigration is often a stark scarcity of skilled professionals at home. A critical example of this occurs in the field of public health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Africa bears more than 24 percent of the global burden of disease but has access to only three percent of health workers and less than one percent of the world’s financial resources.

“Of course there are a lot of smart individuals that have left the country to seek greener pastures and come to the U.S.,” commented Dr. Benjamin Wachina, the President of the African Federation for Emergency Medicine, who spoke with me while he was in New Haven for a panel discussion on the state of medical care in Africa. Within the field of medicine, he believes that this is often due to the limited capacity and resources available in Kenyan hospitals: “The government in our society is not keen to fund research, to do research. You pretty much have to dig into your own pockets to get anything done.” Wachira also pointed out how the shortage of medical professionals creates a self-reinforcing cycle of labour loss. “The challenge… is [that] because of the shortage of healthcare workers, they are stretched — they don’t have the luxury of time to do research.” For those keen to delve into medical research, governmental or societal pressure to remain in Kenya may force them out of the lab and into the hospital ward.

A constant refrain throughout our conversation was a concern that young people in Kenya should be free to explore their options, just as students are in the global North. “I’m even reluctant to call it brain drain; people are just seeking greener pastures,” he told me. “The world has become one big global community. And if you are not offering me good employment training, and I’m not comfortable where I am, then naturally I move.” This highlights an underlying issue in the rhetoric around “brain drain” — the fact that a national onus is placed on young people from African countries that is rarely placed on their American or European colleagues. While a Nigerian practicing medicine in France may be considered complicit in the brain drain phenomenon, an American in France rarely faces similar stigma.

Though movement of African students to American universities is pathologized, the travel of U.S. academic visitors looking for “an experience in Africa” is rarely interrogated. Dr. Michael Capello, a professor at the Yale Medical School and co-director of the Yale Africa Initiative, raised concerns that “collaborative projects” between African countries and the U.S. often focus more on what African universities can do for American students than vice versa. “I think the program gets to one of the almost philosophical issues that aren’t always addressed when [universities] are looking to engage collaborators. We need to collaborate on a mutually beneficial and equitable plane,” he told me. All four walls of his office feature photos from his frequent trips to Ghana; a row of little wooden elephants trundle along his bookshelf. He points me towards a photo of a group of Ghanaian students standing outside of the Yale Medical School. “We decided that we would not send any Yale students to Ghana until we had figured out a way to fund their students to come to Yale as well.” While brain drain attracts media attention and outraged sound-bites, Capello focuses on the development of what he calls “brain circulation,” in which colonial relationships between the global North and South are replaced by a bi-directional movement of students across the equator.

In 2006, along with another School of Medicine professor, Elijah Paintsil, Capello launched the Yale Partnerships for Global Health. The initiative partners with the University of Ghana, and aims to enable young medical researchers to pursue careers on the continent by providing personalized training at Yale, as well as support for the continuation of their projects in Ghana.

Capello, whose work focuses on the global health impact of infectious diseases, also chairs the Council on African Studies. Capello told me that he queries the purported financial motive for academics moving north. “People have written a lot and thought a lot about the drivers of brain drain. And the one that commonly comes up is money. But what we observed was different,” Capello explained “When you make a decision to go into academia, you’re making a decision to not be one of the wealthy elite. So they’re making the decision because of something other than financial gain.” Capello thinks that when it comes to Africa’s intellectuals, most make the move north in order to access the resources and facilities that the Ivy League’s massive endowments can provide.

In reality, our very ability to critique our own complicity in brain drain is a liberty that not all students are afforded. While we hem and haw about whether to settle down in Silicon Valley or Abuja or Johannesburg, the unspoken concession is that we’re part of an elite who have the luxury of making that critical choice. Sipping tea in Koech’s house, we discussed the fact that, while many are forced to remain in the north for economic reasons, the Ivy League stamp often gives people the opportunity to “take more risks” with careers on the continent. Although returning to one’s country of origin can’t always promise financial security, a good education and prestigious certificate can free young professionals to pursue non-economic priorities.

“Some people really need to gain economic freedom first,” Koech told me. “But for me, it all boils down to how I was raised. I was raised by my Grandmom, and I didn’t even realize how much it influenced me,” she says with a smile. “We grew up very communally, and that’s why in every space I’ve been in, I’m always like, is everyone okay? I want to build up my community. That’s the responsibility I have.”

Migrating Minds: On the evolving nature of African “brain drain” was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.