We brought Noam home in the middle of a blizzard. Ours was the only car on the street save for the snowplows, their headlights foggy beacons in the wet whiteness. My dad drove slowly, coaxing the brake pedal at every turn. When the car stopped too suddenly, the zipped-up bag resting on my lap bulged and rattled with animacy, whimpering as if of its own accord. I poked my pinky through the mesh of the carrier and felt a ghost of fur, a tickle of whiskers.

I was seventeen years old; he was one year old. He was getting ready to move into our household; I was getting ready to leave it. It seemed like maybe we could help each other out.

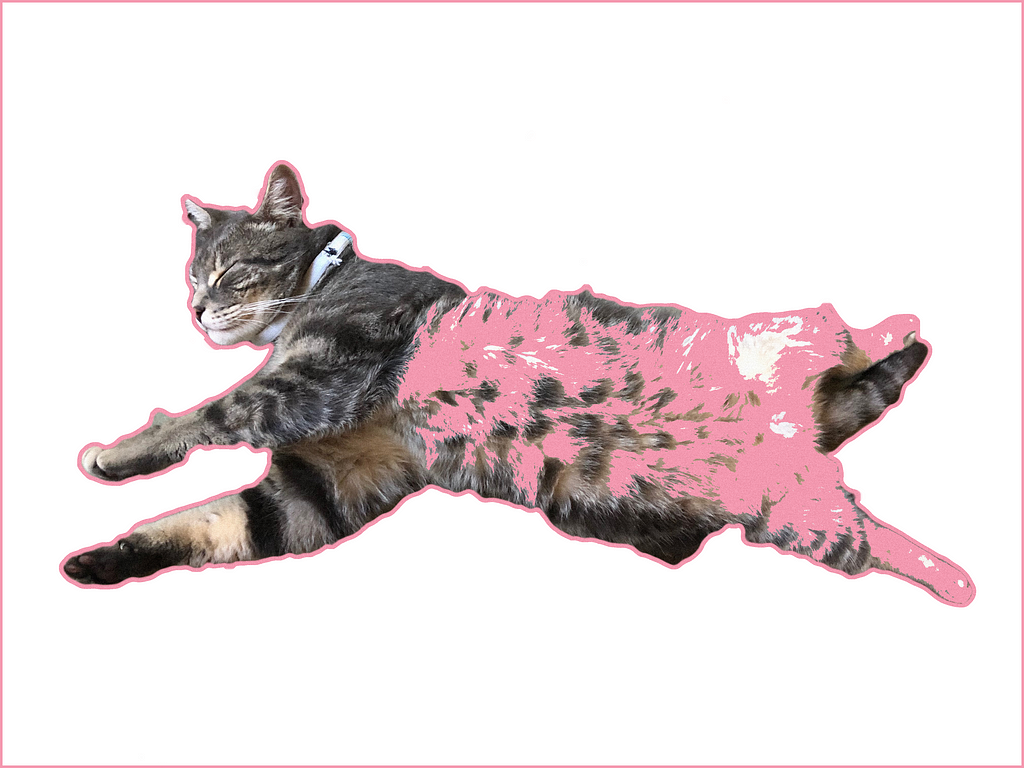

When we got home, my mom and I brought him into the downstairs bathroom, the warmest room of the house. Sitting cross-legged on the tile floor, we slowly unzipped the top of the carrier. A grey head poked out, triangular ears folded flat against it as Noam wriggled his way through the narrow opening. I reached out to pet him, but before I could, he sprung off the floor and straight to the highest shelf in the room. I was struck by how beautiful he was: the smokey lines of grey running symmetrical down his back, feline shoulder muscles rippling as he weaved around bottles of soap and toothbrush holders.

The people at the shelter said we should keep him in a small room for the first few days, so that he could settle in. But he had other ideas, and it seemed pointless to try to rein him in. This would soon become a pattern with Noam.

We argued about the name for days. I, at first, pushed for calling him Sigmund. My dad insisted on Pushkin. We liked the name Kokoschka (Koschka for short), but it didn’t stick. My friend Xueyan suggested we call him Phillip. For long, nameless days, we watched him dash about the house uncontrollably. He wiggled open drawers by himself and figured out how to find and tear open packets of food. When we came home in the evening, the trash drawer would be open and scraps of yesterday’s dinner would litter the floor, bones licked clean. After a few more days of trying and failing to reprimand him without a name, we finally settled on calling him Noam. We weren’t sure why, but it stuck.

His behavior at home was so different from the way he’d acted at the shelter that we worried we’d accidentally taken home the wrong cat. When we first met him, he was sleeping so soundly that he didn’t even open his eyes when we pet him. When I picked him up, he collapsed limply in my arms and hung there like a sack of flour. The people who worked at the shelter described him as “mellow,” saying he would make a great lap cat. But we later discovered, as he broke household items and pounced on our heads when we were least expecting it, that the cat had manipulated us into adopting him. At first, my dad threatened to take him back to the shelter. I protested with tears stinging in my eyes. He was just settling in, I assured my parents. He would change.

I couldn’t explain to anyone, much less to myself, my peculiar attachment to this demon-cat. I would stroke his silky fur as he clawed at my ankles, staring intently into his questioning emerald-green eyes. In those days, I was confused about my place in the world. Having already been accepted to college but not quite done with high school, I was suddenly faced head-on with the pointlessness of my hours of unengaging homework. As I chipped away at my endless physics problem sets, Noam would bite the back of my pencil and refuse to let go. When I spent hours staring at an unwritten essay on my laptop, Noam spread himself across the keyboard. He rolled onto his back, hitting all of the keys at once and sending my computer into a fit. Lying still, he looked up at me searchingly; I tickled his belly, spotted and feathery like the plumage of a baby bird. He pawed at my fingers, leaving red scratch-marks between my knuckles. When he caught my hand in his jaw, I let him, meeting his eyes the whole time. He never bit too hard — he just nibbled, teething on the flesh of my palm the way an infant would. I knew he would never hurt me. His breathing became a deep and steady purr as his eyelids began to drift shut, but he didn’t release his jaw from my hand. We stayed that way for a while, together.

Sometimes, Noam would spend thirty minutes at a time on the living room couch, biting and kneading at our black woolen blanket. When he did this he entered a trance, oblivious to everything around him. We researched this strange behavior online and found that it was a sign that he missed his mama cat, from whom he’d been separated at a young age. When he pawed and suckled at the blanket, he was imagining that it was his mother’s belly. It was through these discoveries that Noam began to make sense to us.

As the hard grey snowbanks on the sidewalk thawed and then disappeared, Noam settled in. He would never sit on our laps, but sometimes he sat next to us on the couch. Every time one of us entered the house, he first came to meet us at the door, purring and rubbing up against our legs. Then, he would run to a very particular spot in the kitchen and collapse onto his back, expecting a vigorous belly rub. And once the sun became a fixture in the warm May skies, he became increasingly preoccupied with the outdoors. For hours, he sat on the living room piano looking out the window, tracing with his eyes the erratic flight patterns of sparrows and cooing almost inaudibly at the squirrels. A few times, he dashed out the door when we least expected it. He always came back, though. He was a smart cat, and knew his way around the neighborhood.

We decided that if we were going to let him outside, he needed a collar. The only problem was that each time we strapped one around his neck, it took him less than a day to remove it and hide it somewhere in the house or outside. He went through countless collars this way. Eventually, my parents resigned themselves to writing his name and our phone number in permanent marker on an elastic waistband and tying it around his neck. He still hasn’t managed to get rid of it.

So Noam and I both began to spend more and more time outside. He would venture to the other side of the street; I would venture to the other side of town to be with my friends. My friends and I suddenly became achingly aware of time closing in on us, and vowed to be together as much as we could for our remaining months. Noam, on the other hand, had nothing but time ahead of him. He spent longer and longer roaming the outdoors unsupervised. One morning, when I was away with my friends in Cape Cod for the weekend, my parents called me.

“We don’t want to worry you,” my dad said, “but we just wanted to let you know that Noam didn’t come home last night. We don’t know where he is.”

I was absent-minded for the rest of that day, deciding to read by myself in some corner rather than spend time with my friends. I wanted to go home. The thought of going off to college and leaving my parents seemed bearable, as long as they had Noam. But without him, I felt they would be utterly alone.

Later that night, they called me to tell me that he had come home. Apparently, he had spent the day at our Russian neighbors’ house. He had been gentle and affectionate, to our utmost disbelief, and the neighbors’ five-year-old daughter had fallen in love with him. Noam began to spend more time at their house, and we let him.

When I moved away to college, my family’s opinion of Noam reversed. My parents gushed about him each time we video-chatted, and they kept the camera trained on him longer than they did on their own faces. Apparently, he now responded to his name, and when my dad said the Spanish word for “eat,” he came running. They told me about all kinds of new strategies they had for dealing with him, including swaddling him in a black blanket, rubbing his nose, and hugging him tightly against their body until he calmed down. “He’s just misunderstood,” my mom said. “He loves us, but he doesn’t know how to show it.”

When I’m home for break, Noam and I find ourselves in a bit of a rough patch. He stalks me through the kitchen when I’m making myself a sandwich, and when I sit on the couch, he pounces on my head and tears at my hair. He doesn’t do this to the rest of my family. When he looks at me, eyes wide and ears perked, he’s asking me a question I don’t know how to answer. I think back to the first days he was with us, close to a year ago, back when I was the only one who would give him a chance. I hope he remembers that, and I like to think he’s just angry at me for having left him.

On this brisk and sunny post-Thanksgiving morning, my dad and I stand drinking coffee on the back porch in our bathrobes and pajamas. There’s a construction site behind our house, where a new three-story condo is being built. We catch sight of a shadow of grey, dashing around parked tractors and rolling around in patches of sun on the uprooted dirt. “Noam!” my dad calls out. “A comer!”

The cat freezes for a moment, meets my eyes in the distance, and then comes running back. He always does.

Wildcat was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.