“Who are you?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“What do you want?”

“To kill you.”

The questioner reaches for his gun, but it’s already too late. Quick on the draw, the assassin’s white-gloved pointer finger squeezes the trigger, resulting in a smoke-filled room, tinnitus from the deafening bangs, and one corpse in lieu of a living person. Thus begins the chain of events that make up the rest of this bad-ass film.

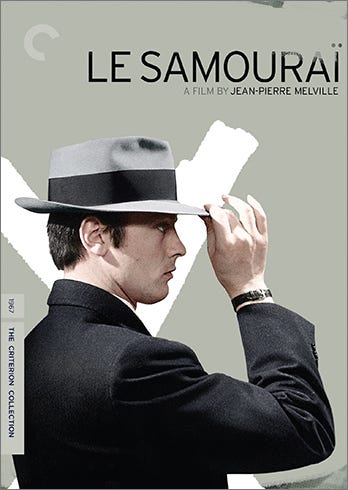

The plot is simple in this seminal 1967 neo-noir thriller: hitman Jef Costello, played by Alain Delon, finds himself pursued both by the criminal underworld and the Parisian police force after a routine hit goes wrong. Simplistic plot aside, the film lends itself to multiple rewatches partly because of director Jean-Pierre Melville’s exquisite sense of aesthetics. Melville combines slick camera zooms and pans with carefully concocted compositions, taking the flexible camera movements of the tradition-eschewing French New Wave and using them in tandem with the carefully planned compositions more reminiscent of the classical style. Each scene is simultaneously a sumptuous photographic feast and a hypnotic display of creative filmmaking at work. In keeping with the story, Melville’s style mirrors Costello’s methodical way of life: he keeps things ordered and acts in a carefully planned manner. Yet, it all feels strangely poetic and graceful due to Delon’s body movements, which are a symphony of free-flowing rigidity.

But the film is mostly riveting thanks to its complex character dynamics, which are buoyed by fantastic acting. Alain Delon, with a career-defining performance, personifies stoic detachment as the title character. His seeming expressionlessness belies a mysterious adhesion to a self-prescribed mode of life, which provides the thematic bedrock upon which the film is built. The straightforward plot imbues the work with a fatalist quality that provokes questioning of Costello’s motives — he could have escaped from the violent life, but why didn’t he? Melville reinforces this question through set design, contrasting the mundanity that Costello subjects himself to with the beauty of escape. The Parisian nightlife is lively, exciting, vibrant. The women wear glossy, sequined dresses. The clubs pulse with energy and jazz music and feature slick, modern interiors that bespeak stylistic pizazz. Costello’s belle and her apartment exude domestic homeliness, the spare decorations indicating a quaint, modest comfort while the woman herself (played wonderfully by Delon’s real-life wife Nathalie) is soft-spoken, yet firm and intelligent, making her a lively and viable exit from a dangerous life.

Yet, Costello remains fixed to his self-chosen way of life, his beige trench-coat and gray fedora barely discernible from the cityscape of rainy afternoons and the carbon-copy sedans that he steals. This sense of lacking identity and self-isolation is expressed through the magnetic opening shot. Costello lies on his mattress in the bottom right corner of the frame, puffing smoke from his cigarette. In the center of the frame is his pet bird, twittering away in a cage on a table in between two light-filled windows. His apartment is dreary, especially compared to the aforementioned sets: the wallpaper is gray and peeling, the walls have no decoration, the lighting is dark, the left side of the frame is crowded with chairs and dressers, and there are no sounds save for the rain pattering on the windows and the high-pitched chirps of the bird. All at once, this shot establishes Costello’s disciplined and ascetic nature as well as the encaged and lonely existence he chooses for himself. If it weren’t for the smoke, we wouldn’t even know he was there. Even the smoke is symbolic of his entrapment: it rises up, trying to move beyond the confines of the ceiling, only to dissipate unceremoniously.

By the time the other sets and characters roll around, we are left with the inevitable question: why is Costello doing this? Why does he cut himself off from society when he so easily could adapt? Is he disillusioned with modern life, unhappy with the consumerism of post-war France? Or, are his actions an altruistic upholding of traditional codes of honor, as the title suggests? To be honest, asking such questions is as fruitless as asking what the ultimate purpose of Don Quixote’s quest was. It was never meant to be answered — answering it would ruin the aura, the mystery, and the magical quality that makes the work so engrossing. Costello only speaks when he must, and even then, his replies are terse and robotic, his voice never giving way to inflection. He doesn’t want people to know his true feelings or motives — he’s a closed book and, because of that, he is ten times more interesting and compelling than any other fictional criminal.

By the end, however, we do find out one thing. We know that what he does want is for people to wonder at him, to contemplate his actions as the audience has implicitly done for the entire run-time. And wonder we shall, again and again; as a fascinating character study and a stylistic tour-de-force, Le Samouraï is a gift that can be reopened in perpetuity, a film that — no matter how many times it has been viewed — leaves its viewer catatonic and awestruck, unable to see cinema in the same way ever again.

Le Samouraï was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.