The history of Asian Americans and their activism at Yale

On a Wednesday morning, the words “Department of Justice,” “discrimination,” and “Asian-American applicants” appeared in a Yale campus-wide email by President Peter Salovey. Like Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard, a case which first rankled the country a year ago, the position of Asian Americans as a model minority separate from other minorities came into question once again. In the email, Salovey defends Yale’s commitment to diversity. He cites an increase in the percentage of Asian Americans in the Class of 2022, from less than 14 percent fifteen years ago to 21.7 percent today.

In 1854, Yung Wing — the first Asian Yale student — attended Yale as an international student from China, long before Asians had become culturally set apart from other minorities in national discourse. He was also the first Chinese person to graduate from a U.S. college. In fact, Wing was an active member on campus, a member of DKE and Brothers in Unity, a literary society. He later organized the Chinese Educational Mission, which sent Chinese students to study abroad in the United States; however, his U.S citizenship was later revoked due to anti-Chinese immigration laws. At this time in the United States, Asians and Asian Americans, like other racial minorities, faced unjust de jure discrimination by the federal government that separated them from white Americans.

Rockwell “Rocky” Chin, GRD ’71, who currently serves as Director of the Office of Equal Opportunity & Diversity at the New York State Division of Human Rights, participated in forming the Asian American Students Association (AASA) while he was a student at Yale. Chin’s family history at Yale extends through much of the 20th century. “Our history goes back to Yung Wing,” he begins, “but since then the position of Asian Americans has grown through time.” In fact, Chin comes from a lineage of Yalies: his grandfather graduated Yale in 1908 and his father, Rockwood Q.P. Chin, graduated in the 1930s. Chin explains in an email, “my own curiosity [about this time period] comes from the fact that my American-born father attended Yale [when] there were only a handful of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders then!”

Yale’s current makeup differs dramatically from its historical reputation as an old boys’ club. Once upon a time, white Protestant males from upper class American families overwhelmed the ranks of each class. As Jasmine Zhuang, GH ’13, aptly describes in the Yale Historical Review, diversity meant only that there was a “small proportion of students who attended public schools.” Facing fierce backlash from alumni, Yale President Kingman Brewster, Jr., implemented initiatives in Yale’s admissions processes to increase the school’s diversity. Minority student populations started to grow.

In 1969, the Asian American Students Association — now called the Asian American Students Alliance — was established as the first iteration of an Asian American Yale student group. Later, in 1981, the Asian American Cultural Center (AACC), one of the four current cultural houses, was established.

Though Chin only attended Yale for two years, from 1969 to 1971, it was “the first time there was critical mass of Asian Pacific Americans at Yale,” which included Don Nakanishi, SY ’71, who was one of the leaders of the formation of AASA in 1969. Although there was a larger Asian American population than ever before, Nakanishi still describes the amount of Asian Americans as a “drop in the bucket” when he attended the school, with exactly 59 Asians at Yale College.

In Chin’s time, there were no Asian American studies courses and no Asian American student groups. Yale had just begun to admit women, and the United States had just begun implementing affirmative action. “We all worked very closely with the Chicano and the Black students.” Chin explains, “At Yale, we all felt we were a kind of minority. We felt somewhat isolated, except when we were together. There were a lot of common issues: ethnic studies, how the University did not relate to the Black communities that worked in New Haven, etc.”

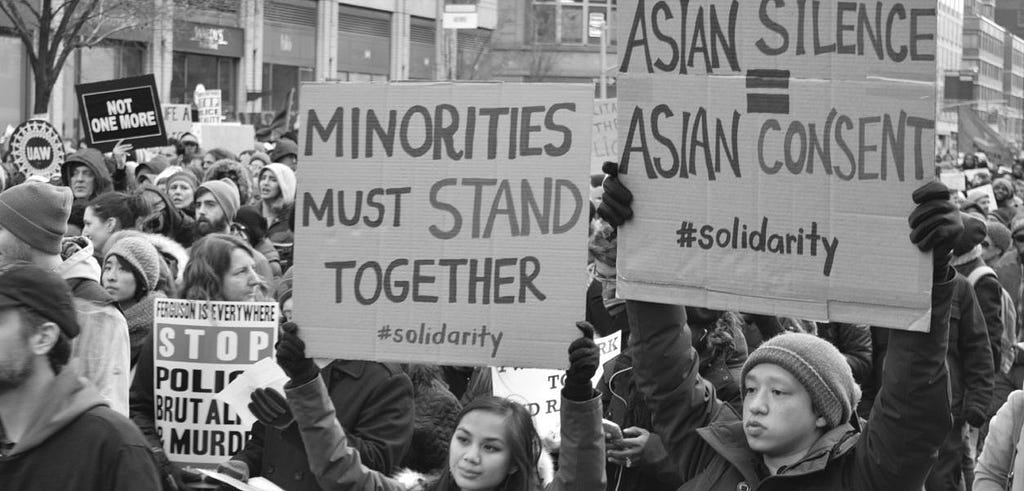

Today’s Yale echoes similar underpinnings of solidarity. Like many of its peer institutions, Yale has grown in diversity. In recent discourse, however, Asian American-ness has been grouped with whiteness and pushed away from other communities of color. In fact, in the Yale Daily News’ staff-written piece, “Our diversity problem,” published on Oct. 29, the News Desk added an editor’s note to reassure that “in pointing out that East Asians are well represented in our Managing Board, [they] did not intend to dismiss the discrimination that East Asians face in accessing top leadership in institutions like the News, or to make the point that they are proximal to whiteness.”

The ongoing debate about Asian discrimination through affirmative action rests on the “model minority” myth — a term first coined in 1966 in The New York Times Magazine by sociologist William Petersen. The “model minority” myth describes the perceived phenomena of a minority achieving higher socioeconomic success than the population average. It has changed the dialogue of Asian Americans in the United States in the context of American race issues. However, the AACC and many — but not all — Asian Americans at Yale still support affirmative action and stand in solidarity with other minorities.

In an official statement, Joliana Yee, Director of the AACC, expresses hope that students “will come to see how a race-conscious, whole-person approach to admissions is necessary to strengthening our communities of learning and a step in the right direction for improving access, equity and inclusion in higher education.” This support for affirmative action is echoed among many Asians on campus.

Kathy Min, BR ’21, an Asian American student at Yale, feels that solidarity among people of color is important and still abundant at Yale. “We’re at a pretty political campus, and many are quite politically conscious,” Min explains. She adds, however, that both solidarity and division have arisen within Asian Americans and other racial minorities on campus. “A lot of Asian Americans are against affirmative action; they have very misplaced anger that it is hurting them,” she notes. The notion that some Asian Americans stand against affirmative action, and thus, other minorities, is addressed in Yee’s email as she tries to dispel the idea that affirmative action’s perceived negatives outweigh its positives.

The AACC still serves as a space for Asian Americans that recognizes the possible difficulties of being a racial minority at Yale. However, the “model minority” myth and public perception of Asian American positionality has contributed to a certain reputation of compliance. Rita Wang, MC ’19, a first-year counselor and former AACC peer liaison, however, notes that she has discussed discrimination with her first-years in the form of microaggressions and stereotypes. “I grew up with the stereotype that Asian Americans were politically inactive and compliant,” Wang notes, “so I was really interested in pushing that notion.” As a peer liaison at the AACC, Wang has noted that it is unfair to say that the AACC is “less activist.”

Reflecting on the AACC, Chin says, “It was a concession by Yale, I think, to address some of the requests and demands of the Asian American students. It did not exist when I was there.” In 1972, AASA was given a one-room office in the basement of Durfee. Four years later in 1977, the East Coast Asian American Student Union founded a Yale chapter, and in 1981, the AACC was established.

AASA is rooted in a history of activism. The creators of AASA advocated for the first Asian American Studies class at Yale, eventually titled “The Asian American Experience,” and in 1971 founded the Amerasia Journal, an Asian American newsletter that is now a premier academic publication in Asian American Studies.

However, even in 1969, Asian Americans came up against the notion that they did not face true discrimination compared to other racial minorities. In fact, in a 1969 statement to the Yale Daily News, Peter M.C. Choy, YC ’69, LAW ’72, explains that one of the most difficult stereotypes that AASA needed to overcome was “that Asian Americans are perfectly assimilated and face no discrimination in American society.” Brewster echoes that statement in a memorandum of the same year that even among those most politically conscious, there is the misconception that “what problems they may have are qualitatively and quantitatively minor.”

Still, this American era was politically charged. It was a time of protests, activism, and Civil Rights conflict. Chin and Nakanishi’s generation became involved in the student movement and the anti-war movement. “By the time I entered Yale, my eyes had been opened to the importance and problems regarding [the] lack of racial diversity, and how student mobilization could work,” Chin explains.

The Asian American Studies course was another example of student involvement. While many Asian American students had actively participated in on-campus political actions through other on-campus minority groups, they felt that academic inclusion was necessary to address the Asian American community’s unique problems and history. Professor Chitoshi Yanaga taught “The Asian American Experience,” but described the course’s creation as a student effort. Choy explains in his 1969 statement that Asian Americans at Yale hoped that the material addressed in the class would challenge the notion that Asian Americans faced little discrimination.

Some Asian American students report that in extracurricular settings, Asian American-ness is unintentionally lumped together with whiteness. Wang, who was former Speaker of the Yale Political Union (YPU), explains that the YPU board “struggled with seeing me as the only woman of color,” often talking to her as if she were a member of the white majority. For students like Wang, the AACC provides a space where the Asian American experience isn’t grouped in with white experience.

Tina Lu, Head of Pauli Murray College, who resides on the Advisory Board of the AACC, notes that the AACC is extremely interconnected with the other campus cultural groups. “The AACC has always been super clear about how it is part of a social world involving other cultural centers, that it is one of many,” she states, reflecting back on the history of Asian Americans at Yale in conjunction with other minority groups.

With the recent affirmative action complaints levied against Yale and Harvard, the original core values of AASA in comparison with today’s manifestation of the AACC and Asian Americans at Yale come under closer scrutiny. Min and Wang both indicate there are some Asian Americans who stand in opposition to affirmative action and the benefits it may give to other minorities. Professor Daniel HoSang, Associate Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity, Race, and Migration, states that there is still widespread support amongst Asian American college students for programs that promote diversity and equality. “The first generation of Asian American Yale students of the 1960s and ’70s were very, very clear that their interests were fully aligned with other students of color,” HoSang explains. “But, of course, any time that groups grow bigger or become diverse — as the Asian American population at Yale has become, there’s going to be ideological and political disagreements.”

The AACC has grown a lot since 1969, when Civil Rights issues dominated the national dialogue and only a few years after the immigration ban was lifted, yet it still retains some essence of its original activist and intercultural origins. “We are in a moment of American politics where everything is at the surface,” says Lu, in reference to racial minorities in America. “All these conversations are coming together in very active ways.”

Even as new types of discrimination, stereotypes, and policies arise, the AACC and AASA continually aim to remain active, heard, and conscious.

The Center Will Hold was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.