Work hard, earn an education and a job and stable flow of money will follow.

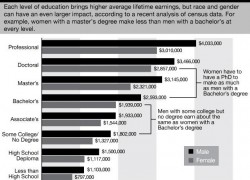

It’s a pillar of American culture, and each level of education has been clearly shown to increase median income after graduation. But according to a new study from Georgetown U., which analyzed data from the U.S. Census, a student’s race and gender are wild cards that impact lifetime earnings more than education or occupation.

The difference is dramatic and persistent. For example, an African American who earns a master’s degree can expect to make as much as a white worker with a bachelor’s. The impact of gender is even larger: A woman must earn a doctorate before she can expect to match the earnings of a man with a bachelor’s degree.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all,” said Ann Mari May, a professor of economics at U. Nebraska-Lincoln who specializes in feminist economics and women and higher education. Equality has improved throughout history and people might think everyone is equal today, she said, but clearly the data disagree.

“The funny thing about progress is that one should never take it for granted,” May said. “There’s nothing inevitable about change … The reality is there’s a long way to go.”

Miguel Ceballos, an associate professor of sociology in UNL’s Institute of Ethnic Studies, echoed May’s lack of surprise, and both agreed on another point: The significant gaps between the different groups comes from a variety of factors.

“Basically, most experts in the field would say it comes from two areas,” May said: choice of occupation and discrimination — in hiring and promotion, for example — once a student gets there. For one, multiple studies have shown that women get lower evaluations than men for the same work, she said, adding, “It’s an institutional-level problem, and it just replicates itself.”

Women also tend to concentrate in different fields than men. According to a report on the status of women released by the White House last year, one-fifth of women are in just five occupations, one of which is nursing.

Meanwhile, men continue to dominate hard-science fields such as engineering, which tend to have higher salaries.

“We know that we’re highly segregated in the labor market,” May said. “Is this because women just choose not to go into (those fields),” she asked, or are women encouraged to go in some directions and discouraged from others?

“I think most people who study this would say it’s probably a combination of both,” she said.

In terms of race, Ceballos also pointed to differences in occupation, with minorities more likely to go into government or teaching jobs, toward the bottom in earning potential. And there’s no denying the power of a history that has included slavery, segregation and discrimination. Race has always mattered in society and continues to matter, and people continue to judge against it, Ceballos said.

“Just because you get a college degree or a law degree doesn’t mean things become equal,” he said. “You can’t just forget about history. It doesn’t disappear.”

Ariel Fullinwider, a junior psychology major at UNL, said she saw the same pattern.

“People aren’t accustomed, sometimes, to minorities being successful,” she said.

Women face the same force of the past, and both groups can lack role models and connections. Women can easily go their college career without seeing a female engineering professor, May said, making it difficult to ever imagine themselves as engineers. Having a diverse faculty at a university would change that and bring in other perspectives, like she does for her own department, she said.

“This is the weight of culture,” May said.

Several UNL students said that matched what they saw on the ground.

“I think it’s pretty much embedded into our society,” said Samantha Jones, a junior family science major who is also Native American.

Her friend, Kendra Haag, also Native American, added, “It’s been traditionally that way.”

Racial minorities face a higher rate of poverty and unemployment, Ceballos said, and politics unfriendly to programs addressing those facts, including affirmative action, aren’t helping. Students who make it to college are often the first in their families.

“So they don’t have family they can kind of fall back on … to navigate the professional world,” he said. “They think their goal is just getting a B.A., that’s the goal.”

What those students do with it is secondary, and their earnings can suffer.

It could be those difficult conditions, however, that turn many minority students to low-paying fields, Ceballos said.

“They see the need for teachers, they see the need for social workers,” he said. “They see it as helping their own community.”

For her part, Jones said she plans on working in the Winnebago Reservation in northeastern Nebraska.

“I see a lack of community support in my community,” she said.

Haag, a junior in biological sciences, felt the same way.

“There’s a lot of health disparities really prevalent among Native American communities,” she said. “I just want to be that person who steps in and help.”

Far from being discouraged by the report, Haag, Jones and Fullinwider said they were still determined, if not more so.

“You can’t let it be discouraging, because what else are you going to do?” Jones asked. “Are you going to give up and drop out?”