Today marks 50 years since the release of the Velvet Underground’s 1969 eponymous LP. It’s also been just over half a decade since the death of the band’s lead singer, songwriter, and creative visionary: Lou Reed. Throughout his life and work, Reed constructed and deconstructed his own masculinity. How Reed dealt with masculinity, femininity, drugs, sex, and everything in between deserves both discussion and commemoration for just how forward-thinking, artistic, and — above all — honest it was.

I was first exposed to Lou Reed’s music in a Johnny Rockets. I was nine or 10, inhaling an Oreo milkshake, when the warm bassline of “Walk on the Wild Side” crackled over the speakers. Reed’s lyrics followed, and the exposure became indecent. The song features a deadpan account of a cast of characters curated from Reed’s time with Andy Warhol’s entourage: Holly, who “shaved her legs and then he was a she”; Candy, who “never lost her head / even when she was giving head”; and New York City — Reed’s favorite protagonist — the place where they say, “Hey babe / Take a walk on the wild side.” The portrait of police officers and firefighters on the wall suddenly seemed less Norman Rockwell and more Tom of Finland.

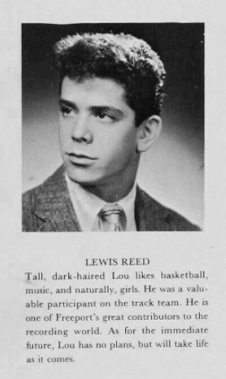

Much of Reed’s childhood probably looked like that Johnny Rockets. His upbringing as the son of an accountant in 1950s suburban Long Island — squeaky clean, family-friendly — proved a perfect backdrop for rebellion. By high school, Reed was playing gay bars on the Island with his band, writing homoerotic poetry, and smoking weed — still taboo, even within the budding youth culture of the time. He began writing. Never one to “go steady,” he attained a reputation for philandering.

Underneath his suave exterior, Reed was troubled. Panic attacks, anxiety, and depression plagued his teenage years. His condition only worsened during his freshman year at NYU, when his parents brought him home in a nearly shell-shocked state. Fearing that their child might be homosexual, his parents — loving, but products of their time — made the ill-advised decision to pursue electroshock therapy. Reed would feel the results of the treatment throughout his life, including short-term memory loss. He eventually resumed his studies at Syracuse University and by the time he graduated in 1964, he was practiced in sexual, musical, and poetic exploration.

After graduation, Reed moved to New York to be an in-house lyricist for Pickwick Records. During a one-off session for a Reed-penned parody song, he met multi-instrumentalist John Cale, with whom he would found The Velvet Underground. Andy Warhol discovered the band at one of their regular gigs on the Lower East Side.

While the world around him was undeniably saturated with creativity and freedom, Reed’s innovative spirit was present long before he joined entered Warhol’s scene. Let’s look at “Heroin,” off The Velvet Underground’s 1967 album Velvet Underground & Nico (ethical concern: it just happens to be my favorite song). Musically, the song features two chords played ad infinitum. In lieu of harmonic change, the tempo mimics a user’s heart rate while shooting up: speeding up, slowing down, ready to explode. Cale’s screeching electric viola punctuates the track, and it’s perhaps the gnarliest sound ever put to tape. Lyrically, it’s scarily lucid:

’Cause it makes me feel like I’m a man

When I put a spike into my vein

The song was written in 1964. In ’64, the Beatles were singing “Can’t Buy Me Love” in suits on The Ed Sullivan Show, and Leave it to Beaver had only been off the air for less than a year. No monikers or nicknames, no “Mary Jane.” Reed is talking about heroin, the drug he injects into his bloodstream to get high, the drug that’s killing him. It’s seductive, it’s honest, it’s terrible. Years before the Summer of Love with its romantic, tune-in-turn-on-drop-out conceptions of drugs, Reed was already over it. Forget diamond-lined skies, Reed was face down in a gutter. Sharon Tate was dead, Hendrix was dead, Bobby Kennedy was dead.

America hadn’t even begun to be culturally de-flowered, yet Reed was burning his floral print and buying a leather jacket.

This is evident even in songs covering more traditional rock ’n’ roll material. “Pale Blue Eyes,” off 1969’s Velvet Underground, is a classic affair-with-a-married-woman confessional. In its archetypal form, the narrator is a masculine conqueror who sleeps with women while their husbands are at work. Drawn from a real relationship, “Pale Blue Eyes” is neither regretful nor celebratory of its affair. It is modest, painful, and candid. Absent is the machismo of the “Back Door Man.” Love was not a conquest to Reed, even when it was a sin. And in Reed’s youth, the love he engaged in was often quite sinful.

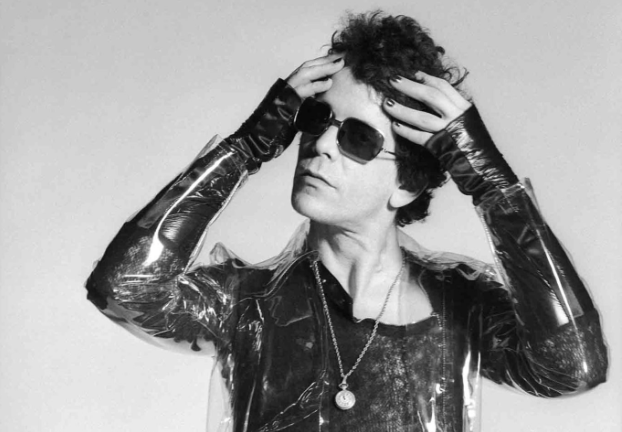

While the San Francisco flower-in-your-hair culture dominated the collective memory of the mid-to-late ’60s, a very different world was budding on the East Coast in Lou Reed’s life and music. He frequented sex clubs like the Anvil, Plato’s Retreat, and the Eulenspiegel Society, a suit-and-tie BDSM society. These sadomasochistic interests permeated Lou’s lyrics, especially salient in “Venus in Furs,” from Velvet Underground & Nico.

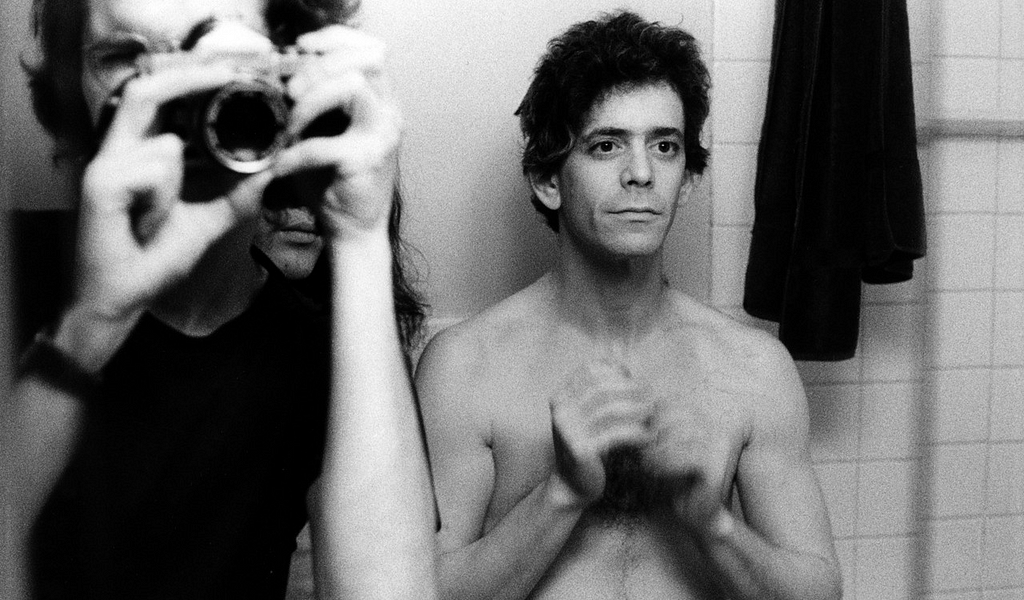

The seedy underbelly of the city fascinated Reed. He was both voyeur and subject, interviewing transsexual people, photographing clubs, and taking friends on “expeditions” through the night. In his personal life, he had relationships with men and women alike, living with a trans woman named Lauren for a few years. Reed treated relationships, sex, and masculinity in his work with a sense of simultaneous distance and intimacy. Just as femininity, sex clubs, and drugs were something to look at, so was masculinity. Take “Candy Says” off the self-titled Velvet Underground. Candy Darling was a trans woman who Reed met while part of Warhol’s world. The song explores themes of body dysmorphia and the inner struggles of being a trans woman in a time even more hostile towards non-binary folks than today. The song’s chorus longingly exclaims:

What do you think I’d see

If I could walk away from me

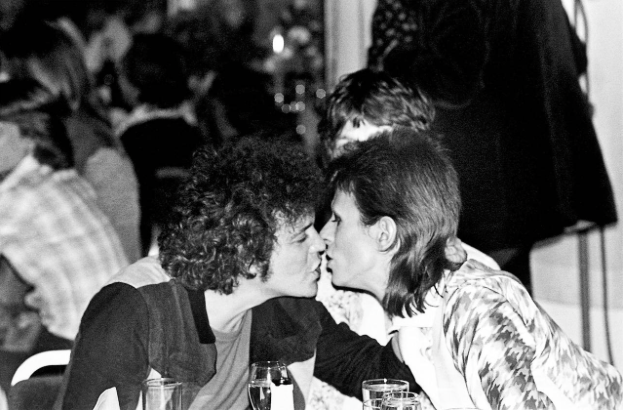

In this short life, one’s own identity is simply one of many pulpits from which to view the world. And one could only imagine what they’d see if they could step outside it. Reed’s explorations of identity — from rocker to strung-out junkie to effeminate songster to middle-aged man — are further evidence of this belief in fluidity. Unlike his most comparable contemporary, David Bowie, however, his explorations were never characters. There was no Ziggy Stardust, there was no White Duke, there was only Lou.

The understated beauty of his lyrics, the ceaseless boundary-pushing of his compositions, the undying rock ’n’ roll spirit that characterized Lou Reed all reflect a dialectic vision of the world: everything and nothing, beautiful and ugly, infinite and claustrophobic.

Reed was a schlub from Long Island who also happened to be one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Reed’s version of love, of life, and of masculinity was devoid of any sense of machismo. He was never Robert Plant, linen-shirt open, on stage soaking the crowd with a flick of his wrist. When The Velvet Underground closed up shop in 1970, he moved back in with his parents. He was never a cavalier perusing the New York nightlife with a sense of empowered aloofness, he was that world. He lived what he sang about: drug addiction, free love, hopeless love, body dysmorphia, botched medical operations, being a sad sap washed up rock star living in your parents’ basement at 28 years old.

As the world changed and Giuliani cleaned up New York and rock ’n’ roll died and was reborn and died again and the trans existence received (at least partially) the dignity it deserves, Lou was still Lou, taking it all in. In Reed’s last statement in his last interview before dying from liver cancer in 2013, he concluded: “There are nature sounds that are whooooo. The sound of the wind, the sound of love. Whooooo.”

Like the wind, like love, like life — ephemeral and passing. Rock ’n’ roll.

Lou Reed: The Man, The Mirror, The Music was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.