When people ask me what I like about Black Mirror, I tell them that I’m drawn to the show’s dark, satirical tone and its forecast of a technology-induced apocalypse. But, while Black Mirror storylines play like nightmares fraught with the most frightening and ethically-questionable uses of technology, its episodes contain, like many lived-through horrific experiences, moments when things seem to have the potential to start looking up–moments when protagonists are presented with a choice. Dismayingly, or, as some might say, inevitably, the protagonists choose incorrectly. But the choice, or at least some semblance of choice, is still there.

Those who expected a new season of Black Mirror this winter were instead surprised with an interactive, standalone film, “Bandersnatch.” The latest installment capitalizes on the longing for choice and the subsequent longing to reverse choices made, and then ultimately turns these choices over to us, the audience.

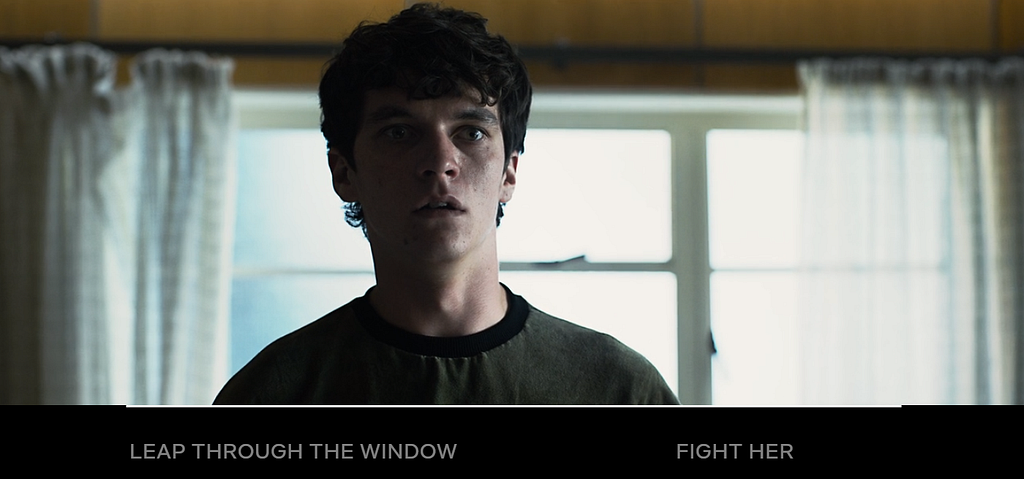

The protagonist of “Bandersnatch” is a young programmer named Stefan, whose ambition is to create the perfect video game adaptation of the episode’s eponymous “Choose Your Own Adventure” novel. The film itself adopts this interactive framework, as showrunners Charlie Brooker and Annabel Jones present the audience with a series of binary choices, which serve to dictate the protagonist’s behavior. When Stefan sits down for breakfast, the audience chooses what cereal he will eat. When Stefan takes out his DVD player on a bus ride, the audience picks the music he will play. When Stefan goes to a record store, the audience decides what vinyl he will buy.

These minor decisions are just a warm-up. They let audience members adjust their viewing habits to Netflix’s new interface before the choices posed to Stefan escalate in both scale and consequence. Stefan becomes obsessed with all aspects of Bandersnatch. He laments the errors in his program, his frustration so visceral that neither choice in Brooker’s binary branches seems rational. The audience must decide between Stefan smashing his keyboard or Stefan spilling tea over his computer and destroying all his work. After navigating more pathways, it also becomes clear that no single choice or combination of choices lends itself to a particularly cheery outcome. This, however, feels familiar. As with almost every Black Mirror episode, there exist only bleak endings and bleaker ones.

In taking on this interactive format, “Bandersnatch” screams novelty, but sacrifices one of its principal traits. Black Mirror has an uncanny, if not exemplary, way of tying together complex storylines in endings that feel complete, even if despairingly so. After a regular season release, fans usually flock to their internet haunts to comment on its despair. But, after “Bandersnatch,” flowcharts mapping Stefan’s possible pathways flooded Twitter. Unfortunately, this multiplicity of “Bandersnatch” lightens the weight of each ending and the summation of endings falls short of packing the show’s usual punch. Viewers are given ten seconds to pick between choices, which makes Stefan’s decisions become marked pauses in the film’s runtime. The clickable decisions for Stefan that appear on our screens diminish the believability of the filmed scenes and remind us that we are watching events play in a fictitious world. And, in fictitious worlds, we have less at stake.

In “Bandersnatch,” Black Mirror writers eschew plot immersion in lieu of creating a meta-commentary on free will and the medium of television itself. This is not to say that the episode doesn’t lose all of its characteristic sharpness. At one point, Stefan asks his programmer idol, Colin Ritman, which ending of the Bandersnatch book he got. To this, Ritman cheekily replies, “all of them.” Other moments see “Bandersnatch” breaking the fourth wall or basking in a doozy acid trip that unfolds like an homage to Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception.

It is difficult to play through “Bandersnatch” without feeling as if the control given to you comes with an eerie sense of cruelty. Such is the case when you have the power to dictate someone else’s decisions from the comfort of your own couch. The audience plays God to Stefan’s fate, a role that grows increasingly wearying as one runs into more dead-ends and less-than-optimal outcomes. The ability to choose is less exciting when there appears to be no way to choose better. Even the chance to reverse decisions, like going back to the point of last save in a video game, brims with futility. This, of course, plays directly into the hands of Black Mirror and its nihilistic tendencies.

A day after the episode came out, my friend joked over text about the number of people who must have spent hours trying to get to each ending. To this, I replied, “ha. totally not me.” But, the fact was I had indeed spent ample time trying to get Stefan to an ending that might break, or at least brush against, the show’s nihilistic seal. When Stefan is offered the choice between chopping up his father’s body or simply burying it in the garden, I realized that I should just cool it with the optimism.

“Bandersnatch” is said to have two and a half hours of unique footage. Its official runtime is listed as one and a half. At this point Netflix gives viewers the option to skip to credits. I suppose that the writers expected people to tire from watching their protagonist bang his head against the wall and decided to give them the choice to exit.

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.